At the end of July, the president of the United States’ suggested that he might delay the November election, a statement that resulted in a great deal of media attention and earned him rebukes from Republican Party leaders and secretaries of states (the officials who administer elections in the U.S. states).

While the president clearly lacks the authority to alter the presidential election calendar, the statement fits with a broader tactic of the president and his allies casting doubt on the integrity of election, and his frequent claim that mail-in ballots are “rigged."

With only three months until the November 3 election, the Republican Party-controlled U.S. Senate appears uninterested in offering election administration assistance to the states despite the enormous challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis, which includes a surge of mail in ballots that will be arriving before Election Day, as well as managing voter safety at polling places with fewer polling workers. If the types of Election Day problems experienced in the primaries are replicated in the general election, the results in swing states like Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin might not be known for some time and cast doubt on the outcome. Indeed, if the results are as close in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin as they were in 2016, there will be strong partisan incentive for state legislatures to intervene, as they attempted to do in Florida in 2000.

State legislators could decide the 2020 presidential election

States are required to certify their presidential elector votes by early December. If the results of a state’s presidential election are disputed or undetermined by this deadline, Article II the Constitution allows the electors to be chosen “in such a manner as the Legislature thereof may direct.” This means that state legislators could play a pivotal role in determining who wins the presidency.

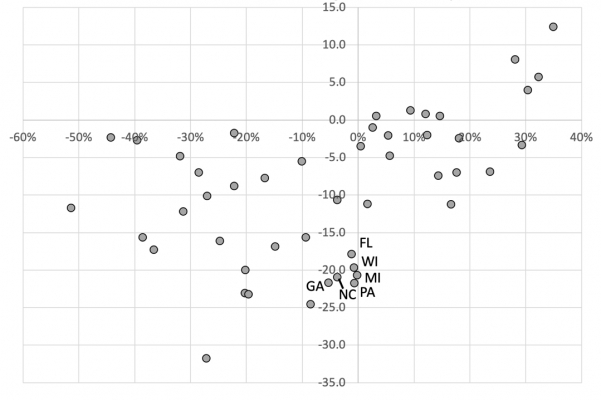

In a forthcoming book on gerrymandering in state legislatures, we find that dozens of states use state legislative districts maps that give the Republican Party an unfair electoral advantage. Many of the states with the most gerrymandered state governments are up for grabs in 2020 and could ultimately determine who wins.

Figure 1 shows the Clinton minus Trump vote margin in 2016 and the advantage that a party has in representation, as a result of the way that legislative districts are drawn. In Michigan, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Wisconsin, the Republican Party rules by virtue of partisan gerrymandering because they controlled how the lines were drawn back in 2011. In 2018, majorities of voters in those states supported Democratic candidates, but Republicans won 53%, 55%, 55% and 63% of legislative seats, respectively. We also find extreme gerrymandering in Florida, Georgia and other states that may be close this November.

If presidential election results are disputed or otherwise not certified in these states by early December, those legislatures could send Republican electors to the Electoral College, even in the face of evidence that Biden actually won the vote. Or, as in 1876, states could end up sending competing sets of electors to Congress. Since 1933, it is the newly elected Congress that would decide the result in a disputed presidential election, so the outcome could depend on which party controls the next Senate.

The House of Representatives could also decide the 2020 election

Even if the Democratic Party were to win control of the Senate, refusal to seat contested electors from these states might still result in Joe Biden not obtaining a majority of electoral votes, which could throw the election to the House of Representatives. Indeed, there is no clear constitutional resolution to how an Electoral College dispute would be decided in Congress.

"...we believe that the old maxim in combat sports holds true for voters this November: don’t leave the fight in the hands of the judges."

However, the current House delegation holds exactly 26 states with a majority of Republican delegates, and that would remain true even if Democrats picked up a few new seats in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin. Again, gerrymandering plays an important role.

With one vote per state, if the House of Representatives elected Donald J. Trump president of the United States, it is not just the Electoral College, but a combination of Congressional gerrymandering and a lighter version of the malapportionment (deviation in the ratio of people to representatives) created in the Senate, that would contribute to such an outcome. With the size of the House capped at 435 members, smaller states and their voters are again overrepresented compared to voters in larger states like California and New York.

The distortions in electoral representation caused by the way the U.S. elects state legislatures, the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives are all biased in favor of President Trump’s re-election. True, these are improbable outcomes. If the election were held today, polling averages suggest that Joe Biden has strong leads in Michigan (8.1%), Wisconsin (7.1%) and Pennsylvania (6.6%), and is ahead in North Carolina (2%). Conversely, there is still time for President Trump to rebound and win at least a clear Electoral College victory, if not an outright majority of the popular vote. It is also important to note that election officials in these states are working hard to ensure an accurate count. Nevertheless, we believe that the old maxim in combat sports holds true for voters this November: don’t leave the fight in the hands of the judges.

This article was originally published at the LSE U.S. Centre's blog on American Politics and Policy.