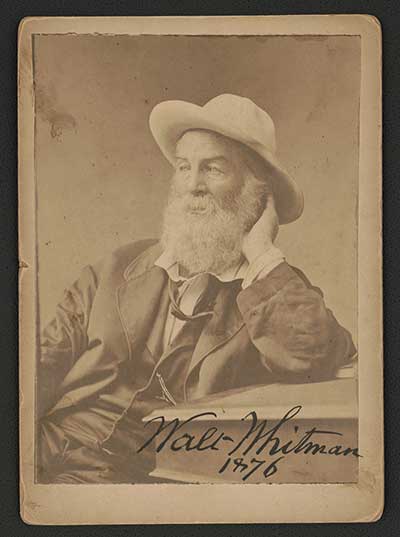

We have frequently printed the word Democracy. Yet I cannot too often repeat that it is a word the real gist of which still sleeps, quite unawakened …. It is a great word, whose history … remains unwritten, because that history has yet to be enacted. (Walt Whitman, "Democratic Vistas," 1871)

The idea of democracy as “yet to be enacted” might strike some Americans as puzzling. After all, American voters have been electing people – from sheriffs, school board members and city councilors to mayors, governors, congressional representatives and presidents – for more than 200 years. (If we count the colonial era, almost 400 years.) But of course the realities of American democracy over the years have left much to be desired. Whitman wrote these words in 1871, a year after the Fifteenth Amendment (ostensibly) granted the right to vote to formerly enslaved persons, and nearly 50 years before the Nineteenth Amendment granted women the vote.

The right to vote is a cornerstone of democratic regimes, and Americans rightly express concerns about measures that make casting votes more difficult or cumbersome. The recent passing of Rep. John Lewis reminded a new generation of Americans of the extraordinary sacrifices made by civil rights and voting rights activists, culminating in the 1965 Voting Rights Act. All of the contributors to this website agree EVERYONE SHOULD VOTE ON NOVEMBER 3.

But even as we seek to encourage voting, and to increase turnout despite being mired in the midst of a pandemic, it may be worth returning to one of the great American poets and political thinkers for some perspective. For Whitman insisted in "Democratic Vistas" that focusing solely on the logistical and competitive nature of election campaigns, and the discrete act of voting (choosing between proffered alternatives), gives us only a partial picture of the broader aspirations so many of us hold for American democracy. Democracy is not simply a set of procedures for choosing public officials; it is a way of life, something that both incorporates and beckons beyond those participating in it at any given time. Too often, he wrote, when people think about democracy, they think about it merely as a procedure for selecting those who will be in charge, and those who get to make the rules. But if democracy is going to become a living and permanent part of our culture, a real fixture in the fabric of everyday American life, we need to think about what happens the day AFTER Election Day, and the day after that, and in the weeks and months that follow. If we confine our focus and concern for American democracy simply to the casting and counting of votes, he suggested, we will have missed something important about the ideal of democracy:

Did you … suppose democracy was only for elections, for politics, and for a party name? I say democracy is only of use there that it may pass on and come to its flower and fruits in manners … in religion, literature, colleges, and schools -- democracy in all public and private life.

Elections, and politics – even democracy itself – then, are means to a larger end. What might that larger end be? What does this phrase – “democracy in all public and private life” – really mean? (Members of the VCU community, especially, might reflect on what democracy in colleges and schools might look like.)

"Democracy is not simply a set of procedures for choosing public officials; it is a way of life, something that both incorporates and beckons beyond those participating in it at any given time."

In "Democratic Vistas," Whitman presented an expansive vision of what American democracy might one day look like, and of its potential to transform individuals, institutions, and nations. Indeed, the theory of democracy implies a much richer understanding of the role of government and what it is capable of in the formation of its citizens. Democracy rests on the presumption of human dignity and human potential, and thus democratic governments ought to aspire to

develop, to open up to cultivation…that aspiration for independence, and the pride and self-respect latent in all characters. I say the mission of government [is] to train communities … beginning with individuals…to rule themselves.

It may begin in a voting booth, for many of us, but it shouldn’t end there, at least not if we are serious about enacting democracy in our own time.

Twenty-first century Americans sometimes view the challenges of reinvigorating American democracy as unique to their context, assuming that their time is uniquely cynical, their politics and society uniquely dysfunctional when compared with other times and places. For sure, 2020 has been no picnic. Whitman published "Democratic Vistas" in the run-up to the U. S. centennial celebration, yet he hesitated to join in his fellow citizens’ enthusiastic euphoria about their young nation’s achievements. True, he pointed out, the Union had recently put down a secessionist movement and enacted constitutional amendments outlawing slavery. But notwithstanding all the promise, Whitman’s view of his contemporaries was profoundly critical. He called on Americans to look at their society like a doctor examining a patient:

We had best look our times and lands searchingly in the face, like a physician diagnosing some deep disease. Never was there, perhaps, more hollowness at heart than at present, and here in the United States. Genuine belief seems to have left us. The underlying principles of the States are not honestly believed in… nor is humanity itself believed in…. We live in an atmosphere of hypocrisy throughout. The men believe not in the women, nor the women in the men. A scornful superciliousness rules in literature. The aim of all the littérateurs is to find something to make fun of. A lot of churches, sects, &c…. usurp the name of religion...The depravity of the business classes of our country is not less than has been supposed, but infinitely greater. The official services of America… are saturated in corruption, bribery, falsehood, maladministration; and the judiciary is tainted. The great cities reek with…robbery and scoundrelism…. In business… the one sole object is, by any means, pecuniary gain.

So even in the midst of a great democratic experiment that was attracting the attention of the entire world (and, to be sure, the United States continues to attract the attention of the world, for better or worse), Americans were shallow, greedy, and selfish, mired in conflict with each other along a wide range of dimensions. Look at some of the terms he uses to describe American society in 1870, and see whether you don’t also hear echoes of the same critiques even today.

But that downbeat assessment is hardly the end of the story. Return, then, to the passage with which I opened. American Democracy, despite more than 200 years of national elections, “sleeps, quite unawakened,” its history “yet to be enacted.” What we do on November 3 is one step in the process of enacting American democracy. Developing a culture of democracy doesn’t happen overnight, and it doesn’t happen in one election. But Election Day is part of the process, to be sure.

So perhaps we should consider this Election Day not merely the culmination of something (campaigns, debates, phone banks, get-out-the-vote efforts), but also as the beginning of something: the first step toward, at long last, enacting the history of American democracy. Vote, of course, and get your friends to vote. But remember that even though Election Day is November 3, the enactment of American democracy begins November 4. After all, as Whitman brought his "Democratic Vistas" to a close, he offered his view that “while many were supposing things established and completed, really the grandest things always remain”; our work, he concluded, “is not ended, but only fairly begun.”

About the Author

Andrew Murphy, Ph.D., researches the intersections between politics and religion in both historical and contemporary contexts. He is particularly interested in the emergence of religious liberty and liberty of conscience in early modern England and America, and the ongoing ramifications of these debates in contemporary American politics.

In recent years Murphy has focused on the life, career and political thought of William Penn, a figure who brought political theory and practice together in the early modern British Atlantic. He is the author of "William Penn: A Life" (Oxford, 2019) and "Liberty, Conscience, and Toleration: The Political Thought of William Penn" (Oxford, 2016). An edition of Penn's political writings for the Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought series is forthcoming. His work on Penn continues the exploration of these topics begun in his first book, "Conscience and Community: Revisiting Toleration and Religious Dissent in Early Modern England and America" (Penn State, 2001).

In more contemporary terms, Murphy is co-author (with David S. Gutterman, of Willamette University) of "Political Religion and Religious Politics: Navigating Identities in the United States" (Routledge, 2015) and of "Prodigal Nation: Moral Decline and Divine Punishment from New England to 9/11" (Oxford, 2008). He edited the "Blackwell Companion to Religion and Violence" (2011) and "Religion, Politics, and American Identity: New Directions, New Controversies" with David S. Gutterman (Lexington, 2006).