The AI Revolution Comes to Campus

How do you prepare students for an AI-transformed world? Teach them to think critically about the technology, not just use it.

Artificial intelligence isn’t coming — it’s already here. It’s in the algorithm that decided which songs played during your morning commute, the system that flagged a suspicious transaction on your credit card, and the tool that autocompleted your last email. For most of us, AI has slipped into the background of everyday routines, invisible yet omnipresent.

But at VCU’s College of Humanities and Sciences, we’re bringing it to the forefront.

As universities nationwide grapple with how to prepare students for an AI-transformed workforce, we’re taking a distinctive approach — one that recognizes that understanding AI means more than learning to code. “Teaching AI is not just about technical skills. It’s about preparing our students to be ethical, critical thinkers in a world increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence,” said Catherine Ingrassia, Ph.D., dean of the College of Humanities and Sciences. “By integrating AI studies across disciplines, we’re equipping our graduates to navigate the complex intersections of technology, society, and human values.”

This fall, the College of Humanities and Sciences launched an interdisciplinary minor in AI studies that examines artificial intelligence through multiple lenses — from ethics and digital rhetoric to climate change and governance. Students can choose from 24 AI-focused courses already offered across the college’s departments and schools, building a curriculum that explores both the technical capabilities and societal implications of AI. The goal is to make AI literacy accessible to every VCU student.

The Language of Artificial Intelligence

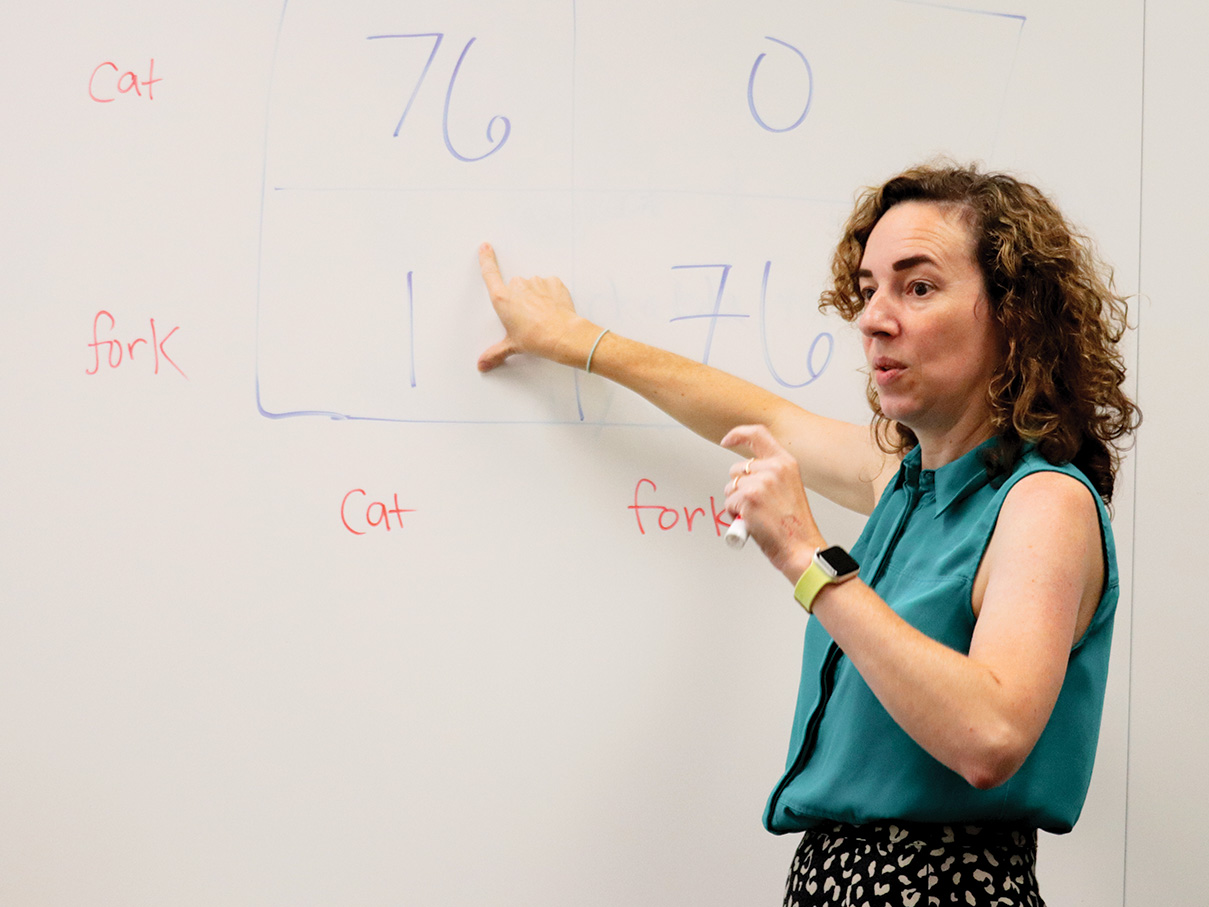

On a table in the front of a classroom stood an odd assortment of coffee mugs, stuffed animals, and office supplies. Allison Moore, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics, encouraged her students to pick an object, take it back to their seats, and log on to the website Teachable Machine. The goal of this experiment was to visually train a computer model on the object, and the first step in the process was to feed the computer information. As students held up their objects and rotated them in front of their computer cameras, the program quickly snapped 30+ photos, creating a digital data set. Next, the students had to test the model. If they showed their computer a mug other than the original, would the computer model be able to identify the object? Or would the computer model mistake it for a bowl?

Moore explained to the students that the computer model is implementing a machine learning algorithm in the background. “In machine learning, we don’t give it all of the data; we give it some of the data,” Moore said. “Some of the images are used to train the model and some of the images are used to determine how good or bad the predictions are.” More photos (and at more varied angles) inserted into the data set would generally provide a more accurate guess as to the object. Later, students learned about a confusion matrix, which explained how the accuracy of the model was calculated, and students played around with different inputs, i.e., the number of photos or the learning rate.

The class, MATH 170: The Language of Artificial Intelligence, seeks to demystify the vocabulary and concepts that are key to understanding the usage and application of AI. For Ryan Jackson, a senior majoring in political science, the course fit perfectly with his future goals. “It’s a recent interest in AI and integrating AI, but I wanted to learn more,” he said. “It’s the number one thing that will change our future in the next few years, and no matter what career pathway I choose, I’m sure I’ll be working with AI.” The fact that MATH 170 fulfilled a gen ed requirement made the course more appealing to Jackson. “Math has been intimidating to me in the past, but with the advancements of AI, a course like this can be really useful. It has real-world applications.”

It’s the Ryan Jacksons of VCU that inspired Moore to teach MATH 170. “I volunteered to teach this class in order to provide a gentle introduction to the mathematics of AI at a level accessible to all students,” said Moore. “The overarching goal for this course is to give students the insight that complex AI systems are, at their core, just mathematical algorithms that can be trained and optimized. AI isn’t magic — it’s math.”

The Ethics of AI

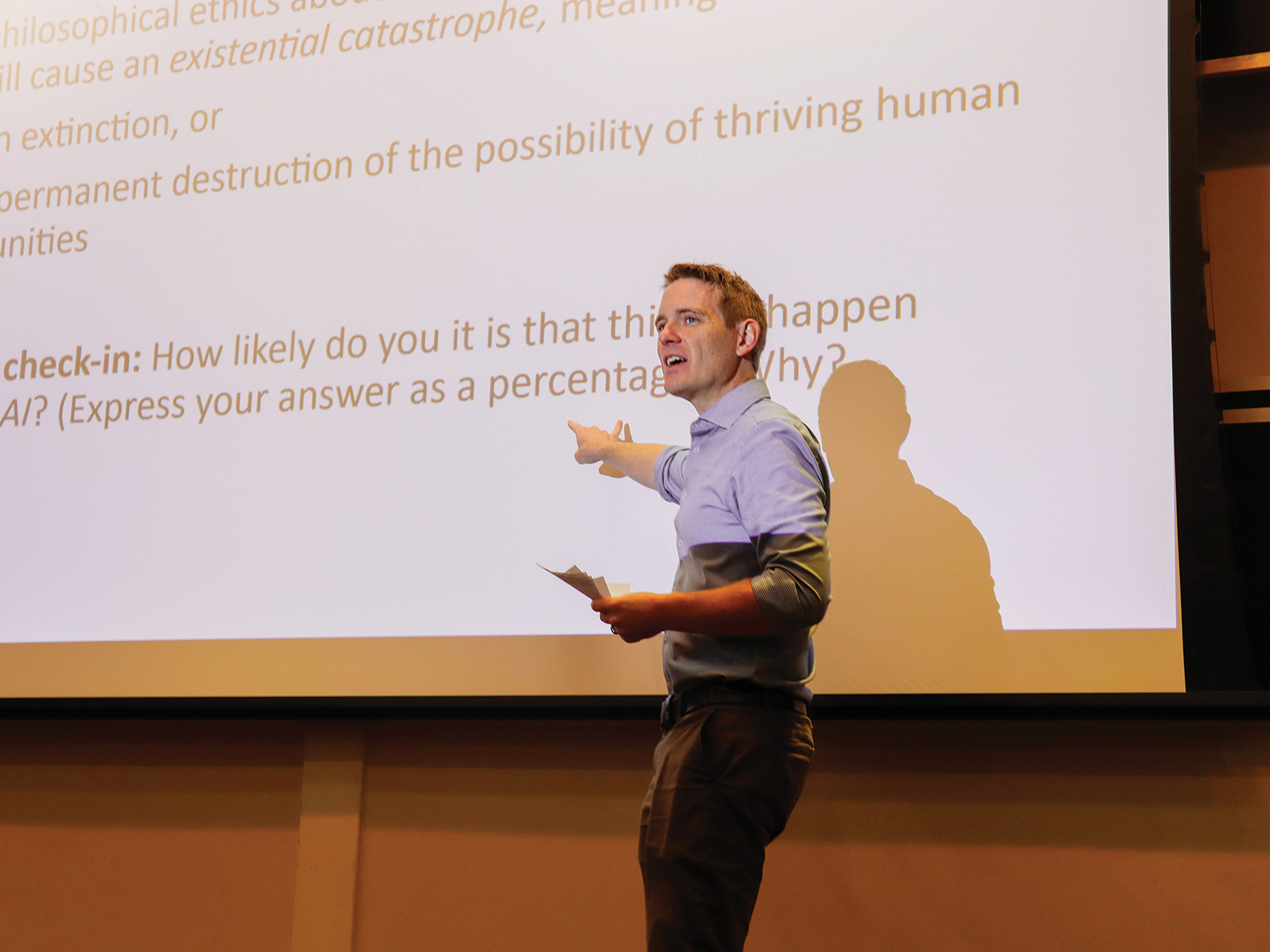

Across the building from the Language of Machine Learning, nearly 100 students were packed into a lecture hall for PHIL 202: Ethics of AI. It’s the most popular AI-focused course at VCU, and the lively conversation in the room was a testament to the growing interest in the moral implications of AI. In this particular class, Jamie Fritz, Ph.D., an associate professor in the

Department of Philosophy, explained algorithmic biases. He began by walking students through hypothetical scenarios to illustrate inductive reasoning. He asked the class: Is it ever reasonable to make a prediction about an individual based on group patterns? Students broke into small groups to discuss, before coming back together to share.

Before long, Fritz was linking those discussion points to issues of AI biases. He showed the class a photo collage produced by a 2023 AI model that was asked to provide an image of an engineer. Spoiler: They were all white men. When AI models tried to correct this stereotype, some (arguably) overshot. For example, when asked to provide a photo of a pope, the AI generated an image of a woman in pope attire. “What is AI supposed to do? Show us a world with bias or stripped of those biases?” asked Fritz.

These are just a few of the questions the class will tackle throughout the course. Others: Is AI capable of thought and reason? Are our lives made worse by AI-driven reductions in data privacy? Who is responsible for choices made by AI? Fritz believes the class is about more than just AI. “I’m energized by the fact that, when we talk about the ethics of AI, we’re very quickly brought face-to-face with some fundamental, burning questions about how to live well,” he said. “Many worry that powerful AI systems are illicitly shaping our choices and our lives. Well, what sort of control over our choices and our lives should we aim to preserve? AI creates tempting shortcuts to certain intellectual and artistic achievements. Well, what sorts of achievements should we want to keep for ourselves, and which should we want to outsource? In short, this class isn’t just a primer on the costs and benefits of various AI applications; it’s also a springboard that can propel students into defining and discovering what really matters.”

The Department of Philosophy was an early initiator in AI discussions on campus. Last year, they created a digital badge for students who take both the Ethics of AI and the Philosophy of AI classes. Digital badges (administered through Credly) serve as verified, online microcredentials and represent the skills and knowledge gained throughout a student’s academic journey that don’t necessarily show up on a typical transcript.

Avery Whitehorne, a biology and philosophy dual major, decided to complete the badge after noticing that “the use and creation of AI was becoming a prominent debate in the world.” For her Philosophy of AI course, Whitehorne was asked to use AI to help complete her semester-long project. “I chose to write my paper on the responsibility of AI’s actions and where the responsibility should fall. Having to do this and work with AI to do it was so interesting because the AI helped us find our topics, our sources, and even planned our whole semester to write the paper,” Whitehorne said. “This assignment changed my thinking and led me to dig deeper into the topic of AI and the problems that are sure to arise from its use and its continued development.”

This kind of experiential learning — where students engage directly with AI tools while simultaneously examining their ethical implications — is precisely what faculty members believe will equip graduates to navigate an increasingly AI-driven world. “AI is very quickly rearranging the social structures within which students work, play, communicate, and learn; it’s also altering the powerful institutions that govern them and the natural world that surrounds them,” said Fritz. “In order to have a solid understanding of the new world they’ll be living in when they graduate, students need to do some careful thinking about the many ways in which AI is already shaping, and can be used to reshape, that world.”

Critical Studies in AI

The students in Jennifer Rhee’s HUMS 392: Critical Studies in AI were learning about snake oil — not the 19th-century version of the word, when traveling salesmen hawked their wares with false claims of success but the 21st-century version: AI snake oil. Rhee, an associate professor in the Department of English, explained that AI snake oil is when AI is advertised in ways that it doesn’t and cannot work. “Conversations about artificial intelligence are led by the tech industry, and they often use AI snake oil to sell products to our government or the medical domain,” she explained. “These products claim to predict crime or job performance, but the reality is that they can’t.” Over the course of the semester, students learn about AI’s relationship to sustainability, labor exploitation, social impacts related to race, gender, sexuality, and disability, and much more.

Students divided into breakout rooms to discuss the readings for class, among them Arvind Narayanan’s “AI Snake Oil: What Artificial Intelligence Can Do, What It Can’t, and How to Tell the Difference,” and Meredith Whittaker and Lucy Suchman’s “The Myth of Artificial Intelligence.” The students were tasked with designing an activity for 8th graders about AI snake oil and AI hype lessons. Abbey Ellerglick, an interdisciplinary studies major, is a student in Rhee’s class. She signed up for the course because she was “simultaneously terrified and fascinated by AI.” From Rhee, she’s learned more about the impact of data centers: “When people say ‘the cloud,’ it’s not something in the air and it’s not mysterious at all. ‘The cloud’ is data centers that are extremely detrimental to the environment.”

Taking the mystery out of AI is one of Rhee’s main goals. “I want my students to become educated decision makers,” explained Rhee. “To know how AI systems work and don’t work, what they can do well and can’t. I want them to discover all the ways that AI systems produce significant labor and ecological concerns that are obscured from how people talk about AI in the media.” Ellerglick, who plans to use her knowledge of AI to inform others, believes the class has done just that. “This class has given me more tools to talk about AI in an educated way,” Ellerglick said. “I feel it’s my responsibility to learn as much as I can and do something positive with that understanding.”

Want to learn more about AI?

The Office of Continuing and Professional Education offers Navigating AI: Ethical Considerations for the Modern Workplace, a three-week, asynchronous online course for alumni and community members. Taught by James Fritz, Ph.D., and Frank Fairies, Ph.D., from the VCU Department of Philosophy, the course delves into the rapidly evolving world of artificial intelligence, examining both its technical foundations and its ethical implications for the workplace. To learn more, visit the OCPE website. Many discounts apply.